This is a second post focusing on surveillance capitalism and how textbook publishers are collecting mass amounts of information about our students that we have no control over. For a primer, step over here (mirrored on Medium.com) and then come back to this post.

During the last week since I published my initial post about student data being harvested by publishers, I’ve learned (or confirmed) a few things:

- Publishers do collect data about our students when they use products such as digital textbooks and homework tools

- The terms of use (TOU) or end-user license agreements (EULAs) for most of these products are hidden (read: not publicly viewable)

- The EULAs are legal contracts solely between the student and the publishers (excluding the education institution and instructor)

- The EULAs grant broad permissions for publishers to buy, sell, trade or use student data for any purpose

If you’re following me, the main issue here is that students are essentially strong armed into agreeing to a EULA so that they can complete a course – they are assigned the book by a professor, so it’s not a student choice. In the case of textbook rental programs (often called ‘inclusive access’), students are automatically opted-in (and charged) for the digital book or tool. The reason publishers offer a discount on these digital rentals is because they have guaranteed numbers of students who are automatically charged. If students opt out within a specific time frame, they can be refunded but it is often not possible to find the required textbook elsewhere. Feeling the pinch, they usually stay opted-in and “accept” the fee and the terms of the EULA which govern how their personal data is collected and used.

Stop sign image by Susan Sermoneta / CC BY-NC-ND

Stop sign image by Susan Sermoneta / CC BY-NC-ND

Students should know how data is being collected about them and how it is being used. Full stop.

As it turns out, the US Federal Department of Education (DOE) shares this belief, and so put together a guide for institutions to make equitable decisions about which educational technology tools they implement. The document is titled Protecting Student Privacy While Using Online Educational Services: Model Terms of Service and is described:

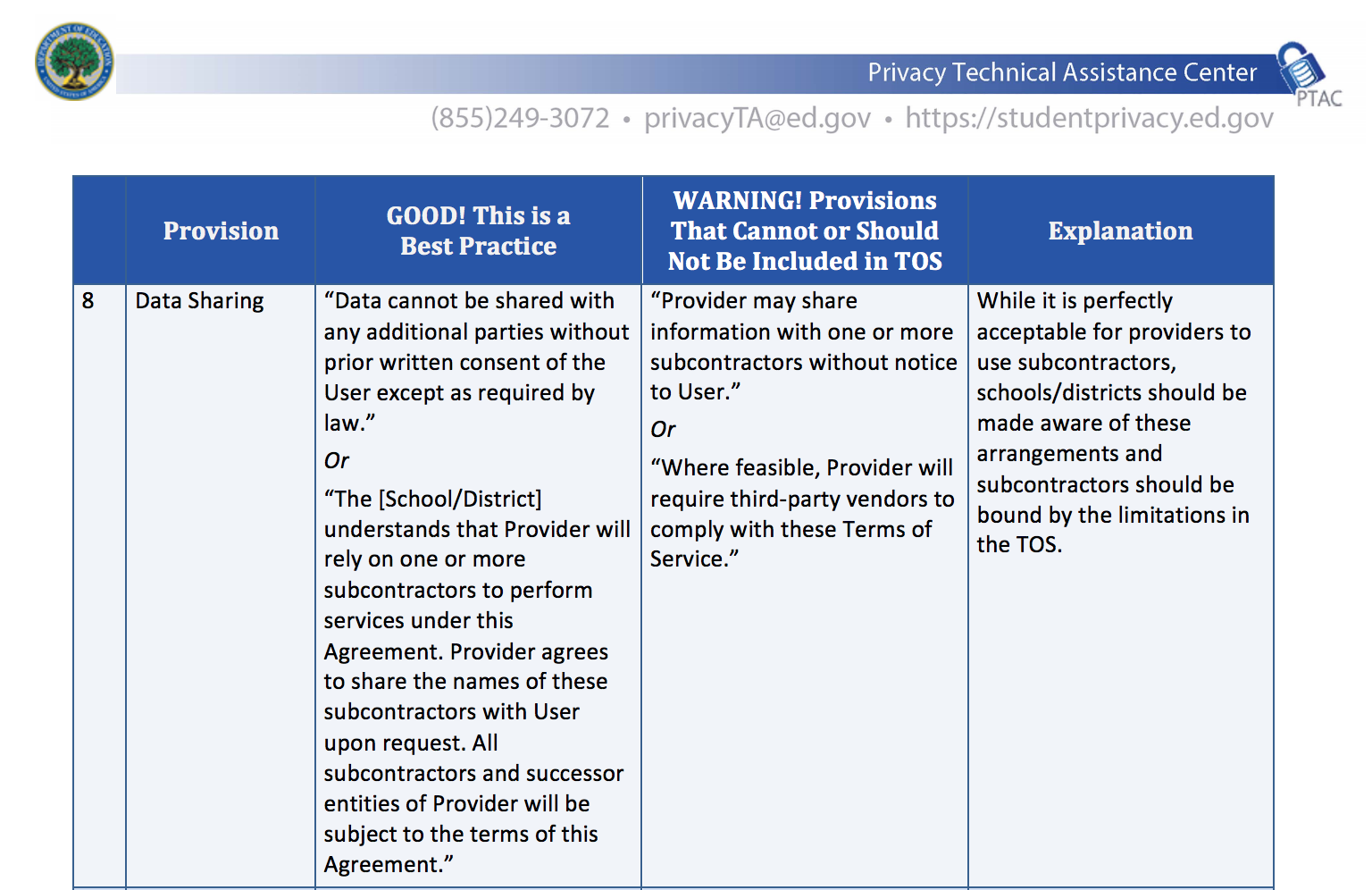

The Privacy Technical Assistance Center, working with the Department of Education’s Family Policy Compliance office, has developed a checklist document that provides a framework for evaluating online educational tools' Terms of Service Agreements. This document is intended to assist users in understanding how a given online service or app will collect, use and/or transmit user information so that they can then decide whether or not to sign up.

This is DOE documentation for best practices, which gives it some authority when it comes to the thoughtful implementation of technology in education. With user (student) privacy at its core, these are the provisions explained in the guide:

- Definition of “Data”

- Data De-identification

- Marketing and Advertising

- Modifications of Terms of Service

- Data Collection

- Data Use

- Data Mining

- Data Sharing

- Data Transfer or Destruction

- Rights and License in and to Data

- Access

- Security Controls

Screenshot of studentprivacy.ed.gov

Screenshot of studentprivacy.ed.gov

The guide has sample text for each of the above provisions that fall under “GOOD! This is a Best Practice,” or “WARNING! Provisions That Cannot or Should Not Be Included in TOS”. This should make it straightforward for institutions to know when the TOS or EULAs associated with digital textbooks and homework tools may be compromising student data. Even if the data publishers are collecting about our students are not explicitly covered under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), agreements that include language that run afoul of these guidelines should be cause for major concern. These are our students, and we need to ensure that publishers are not putting their personal information at risk.

I’ll remind everyone that the data collected by publishers in this way (students using a tool) may not be covered by the data use agreements publishers have in place with the institution. This is data that are actively or passively collected by the publisher while students access their websites and digital tools, fueling their data surveillance business model. Some institutions will be quick to attempt to wash their hands of this situation since it is not data they are granting use of to the publishers. But if the institution won’t step in, who will?

Let’s look closely one interesting provision mentioned in the guide: data sharing.

Under the GOOD! This is a Best Practice section they offer sample text:

“Data cannot be shared with any additional parties without prior written consent of the User except as required by law.”

This seems entirely reasonable. A EULA students sign should make it clear that their data isn’t shared with anyone other the publisher itself. All tools we require students to use should explicitly state this.

Under the WARNING! Provisions That Cannot or Should Not Be Included in TOS section we find this sample text:

"Provider may share information with one or more subcontractors without notice to User."

This kind of blanket permission to share data is exactly what we do not want to be written into the TOS or EULAs of products our students use. “Why?” you ask? The guide is helpful here, too:

"While it is perfectly acceptable for providers to use subcontractors, schools/districts should be made aware of these arrangements and subcontractors should be bound by the limitations in the TOS."

But I’m not particularly worried about sub-contractors (working for the publishers) having access to student data. That would be too simple. What worries me is when TOS and EULAs grant blanket permissions for third parties (other than sub-contractors) to use the data. This freaks me out.

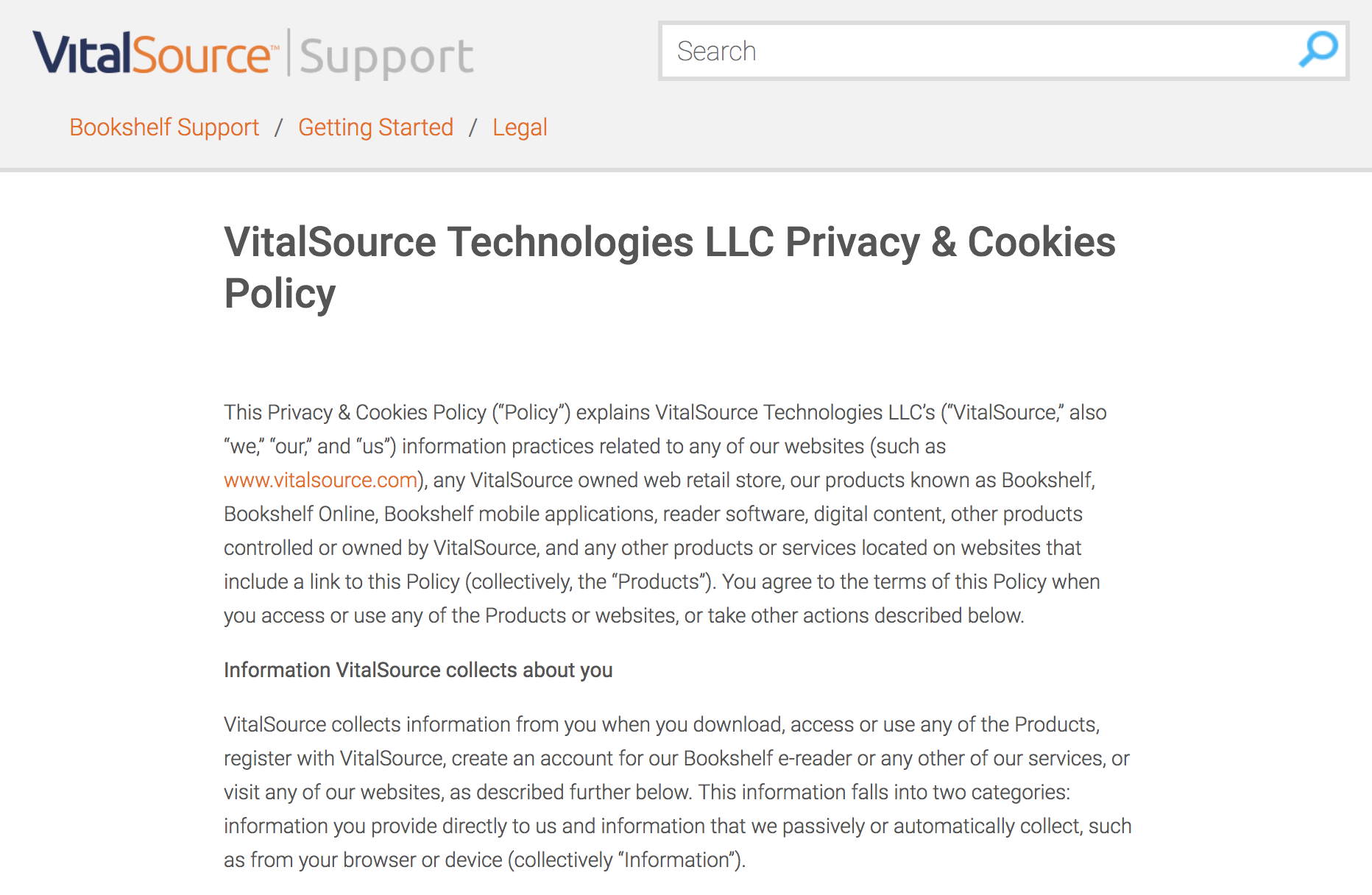

Screenshot of VitalSource’s website

Screenshot of VitalSource’s website

Well, look here at the TOS for VitalSource, a vendor of electronic textbooks and educational technology tools. They are a vendor for the University of Hawai’i inclusive access program, too, so we have some skin in the game. From the VitalSource Technologies LLC Privacy & Cookies Policy:

We may collect Information from you when you access or use the Products, such as when you: create an account, make a purchase, download content, input user-generated content, including notes and highlights in books, participate in assessments, and share information with friends. The types of Information we collect may include your name, address, email address, phone number, other contact information, employer, academic institution, course information, credit or debit card numbers, and user-generated content such as notes, highlights, and responses to assessments.

So, it’s clear that VitalSource collects both demographic and behavioral data about students. But what do they want to do with the data?

...We will collect, use, transfer and disclose this Information as described in this Policy. We may collect, use, transfer and disclose aggregate or de-identified information without any restriction.

Hmm. That looks like a gaping hole in our privacy of our students’ data. A big one.

But it doesn’t stop there.

We may receive similar Information from third parties including public sources, our related companies, your organization, your representatives, information service providers, social media and the parties with whom we exchange Information as described here.

By using their products, you also give them permission to cross-reference your data with data they get from third parties, including the data the institution provides to them. And data brokers. And any social media profiles they can match to you, or that you were logged into your web browser with. Facebook, anyone? Apologies if you sleep poorly after hearing this, but data collected by education publishers is being curated into a massive dataset about you. You, yes you. And this data is exchanged all the time. Under these terms, no student data collected in the use of these products is safe from abuses we are aware of, or that will be thought up down the line.

We could go on, but I want to point out one more part of VitalSource’s TOS that needs to be addressed. Under the section titled VitalSource’s use of your Information, we skip down to the last line. It’s a juicy one:

We may aggregate and/or de-identify Information collected through the Products. We may use de-identified or aggregated data for any purpose and may share it with any third parties.

Well, shit.

Let’s forget for a moment that this TOS doesn’t even explain how your information is de-identified – nor ensuring that it can’t be re-identified after the fact, the likelihood of which increases dramatically with each additional data point about you. Let’s just focus on the permissions we grant publishers like VitalSource when we use their products.

Any purpose. Any third parties.

Think about that for a moment.

This quick examination of the TOS for VitalSource products surely meets the threshold for “possible problems with student data sharing” for any responsible educational institution. If it doesn’t, then frankly I don’t know what to tell you. Universities need to sound the alarm.

But here’s the kicker, as there usually is.

These are the terms that VitalSource made publicly available, the terms they allow us to see. What terms live in the EULAs that students click through? The publishers actively hide these terms. What’s in them?

I’m still waiting for Pearson, Cengage, and the other major digital textbook publishers who syphon-and-sell our students’ data to come clean and at the very least show us their current EULAs. Where we go from there will depend on what’s inside them, but we can’t know until they are surfaced.

Header image by Scott Webb on unsplash.com

Image by

Image by