This is the transcript from a keynote delivered November 11th at the Open Education Ontario Summit in Toronto. Thanks to David Porter, Jenni Hayman, Terry Greene, Lillian Hogendoorn, Ali Versluis, Jessica O’Reilly, and Lena Patterson for facilitating a smooth, engaging event and for giving me the opportunity to share some big, difficult ideas with the Open Rangers.

Aloha mai kākou. (We are together)

Thank you for sharing your time with me this afternoon. Being in Canada for the first time feels sort of like coming home to a place I’ve never been. Part of this has to do with the very warm hospitality of the typical person on the street. The customs agent at the airport told me to break a leg in my talk – and I’m going to try to do just that.

But being in Canada also feels a little like home because I’ve worked in the “open” for a number of years now, and my worldly colleagues from this place on the continent have continually impressed me with their kindness and generosity. The seemingly small, personal gestures that make working in this community worthwhile do not go unnoticed – they signal a sense of shared values. For the next short while here, I’m going to share with you the brief history of me, my work in things you would consider “open” and how I think this community is actually nearing an inflection point where we must hold strong to our values while we face challenges from all angles. The publishing industry does not always appreciate the work we do, obviously. Policymakers are waiting for us to prove that this thing called “open education” actually works. And while this community grows, I’m afraid we are developing an unhealthy tolerance for the lack of empathy and care required for us to appreciate the human aspect of this work… and this absence will divide us more than it brings us together.

It’s also important for me to mention that as a white male, I am given an extraordinary amount of privilege and quite honestly there are others in this room who should probably be at this microphone instead of me, and that would deliver messages I would stand behind without question. This isn’t to say that I’m experiencing imposter syndrome…as I do understand that I have a place in this community and this movement…but that it’s important to listen to many voices, not just mine.

So I live in Hawaii and I work at the University of Hawaii’s Manoa campus, the “flagship” campus of the system, offering undergrad, graduate, and doctoral degrees. I serve as the OER Technologist for the campus, but that title is something of a misnomer because like many titles, it doesn’t reflect the work I actually do. I’m also a first-year PhD student in the political science department, specifically the futures studies program, which has something of a reputation. I figure that even if at the end of this road I conclude that being a “futurist” is not actually a thing, I’ll at least know better how to argue with the tin-foil hats that pop up from time to time. Or I’ll become one of them, I’m not quite sure.

But I wasn’t always working in “open” space, and like many of you I wandered a bit before coming into the work that I do now. Throughout college I conducted one-on-one and group therapy with children with a range of disabilities, from basic language and motor skills to life and interpersonal skill development. Finishing my undergraduate degree about ten years ago, the economy was taking a nosedive and the most stable work available was at an elementary school where I lived in Santa Barbara, California. The school was in a low-income area and served an almost exclusively Hispanic English-Language Learner student population. The school was eligible for grants, and I was tasked with setting up a computer lab that had literally had technology thrown at it. I had no idea what I was doing, but I unboxed the desktops and made friends with the school district IT folks, and somehow figured out how to make the computers do things that the kids enjoyed and that the grade-level teachers valued. This isn’t to say that I had any idea what I was doing, but that was my foray into what I consider to be traditional, institutionalized education. Learning outcomes, teaching teams, teacher strikes, tetherball courts, the whole bit. It was beautiful fun, but at the end of my second year my principal told me to go to grad school, and that she wouldn’t hire me back.

Needing a change of pace for reasons beyond my job, I left for Hawaii and entered the Learning Design and Technology masters program at the University of Hawaii (the same campus I work at now). In what was largely a tech-focused instructional design program that loved itself some ADDIE modeling and gamification, I found a course called “open source in education” and it changed my life.

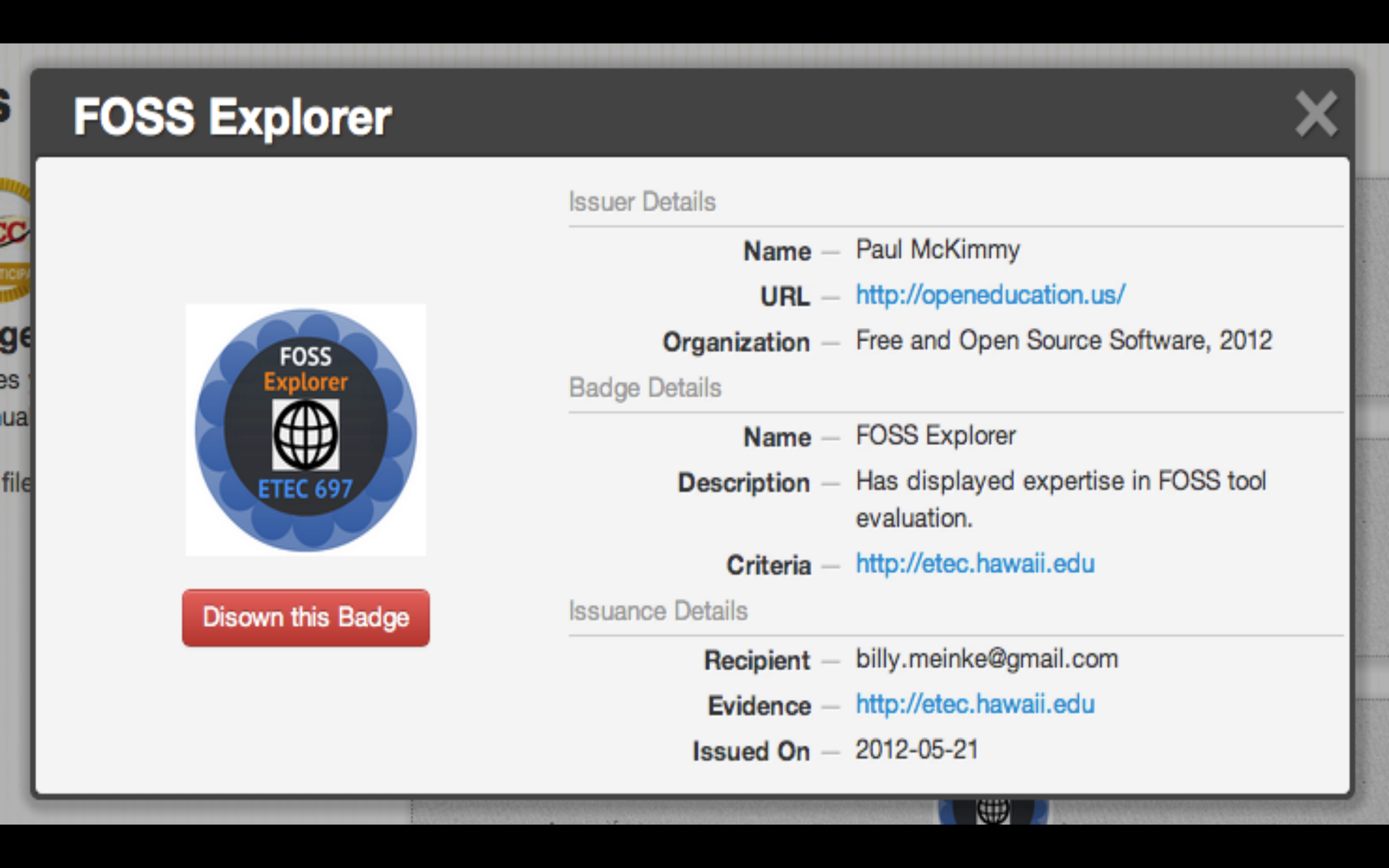

The course required students to contribute in some way to an open source project that had implications in education. The Mozilla Foundation was spinning up its Open Badges project – which is all but non-existent at this point – and I started joining their community calls and working on their documentation. The sense of welcome and open participation was like nothing I had seen before. In many corners of academia we are told to keep our work close to our chests lest we be scooped by a competitor, and it shocked me that such talented people at Mozilla had flipped this paradigm on its head. They had roadmaps and roles and funding and were building a team. I finished my masters degree and painfully left Hawaii for the Bay Area. I wanted to work in tech, and I wanted it to be in the “open” movement.

A few months after relocating to Mountain View, California, I was still jobless and was losing motivation to try to work in the open. Mozilla hadn’t called, and despite offers from for-profit edtech companies, I took the last of my savings and went on a slingshot tour of Europe with two of my best friends. My morale improved and my bank account shrank, but I also found myself only a few hundred miles away from Helsinki, Finland in time for the first Open Knowledge Festival being put on by the Open Knowledge Foundation – now referred to simply as Open Knowledge. I figured, “what the hell,” and volunteered with the event, helping with registration and session facilitation, and immersing myself in the “open” community that gathered there.

Lucky me, folks who worked at Creative Commons happened to be in attendance, and they were looking for an intern to join their science and data unit. Ironically, I was meeting the people at CC more than 5,000 miles away from home, but the room I rented in Mountain View was less than three miles from their office headquarters. Lucky again, I took the internship and entered what I referred to at the time as my personal accelerator. This meant being able to affiliate myself with an organization whose standing in the community was huge…the licenses are the linchpin of the work we do.

During the 14-month internship, I learned about this thing called Open Access, and learned what it meant for “data” to be open. I bumped shoulders with Mozillians once again (woohoo!) and made many friends whose work intersected with mine in the open space. Seeing how the sausage was made was enlightening, but I also paid a price for it. You see, my supervisor was a serial harasser and misogynist, and while I grew in some ways I was also dismantled on a daily basis by this person. You don’t quite understand the power dynamics at play until your supervisor who harassed and bullied you privately and in front of others actively speaks out against your being hired on. Fortunately my community building work around what I think may have been the first MOOC about open science during the internship and my friendly can-do attitude meant that I landed a job with CC. After the announcement of my being hired on as a staff member on the education team, and no longer underneath him, my harasser had the gaul to invite me to lunch and to then tell me about how he spoke out against my hiring. He told me to leave, to go back to school, to just go. I didn’t.

We are all going to have moments in life, if we haven’t already, where wrongs are made against people who are trying to do good work, trying to help push forward this big rock we call “Open”. What we do in these moments will define us, and if you take nothing from this keynote talk, I ask you to not look the other way when it happens near you. Many of us have stories. Some of us have been treated poorly, and some of us have been spared this pain…but may have seen it happen to others. I care more about this community than most, and I don’t just “think” we should do better. I think we MUST do better. Let’s talk about what it means to have spaces that encourage diverse voices to speak, and to allow the work we do in this movement to no longer be considered “on the fringes”.

The writer William Gibson is known for having said that the future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed. I am telling you right now that much of the work we do in open education is the future, and we all have a hand in helping the best parts of it become part of the mainstream.

Let’s return to this notion of the open community being at an inflection point.

Creative Commons champions the notion of the commons being larger than it’s ever been before. In fact they recognize that over 400 million CC-licensed images are on the photo sharing site Flickr, representing about ¼ of everything we consider to be the digital commons. But in a single moment, the powers that be at Flickr decided that their model of offering generous free space for images was no longer working, and they announced a plan to begin deleting images on free accounts that exceed 1,000 images. To keep them all, they said we would each need to upgrade to a Pro account for around $50 per year. Complaints from the community came swiftly and in volume, criticizing the move and calling for a fix. Despite the new promise from Flickr that existing CC licensed images would not be deleted…the message is clear: the technology platforms we rely on are changing and to leave things the way they are is to put our work at risk. To bring this issue into focus, this presentation is a bit of a ticking time bomb as several photos have been linked from Flickr and one day the digital representation of this talk will begin to unravel. I’m sorry for that.

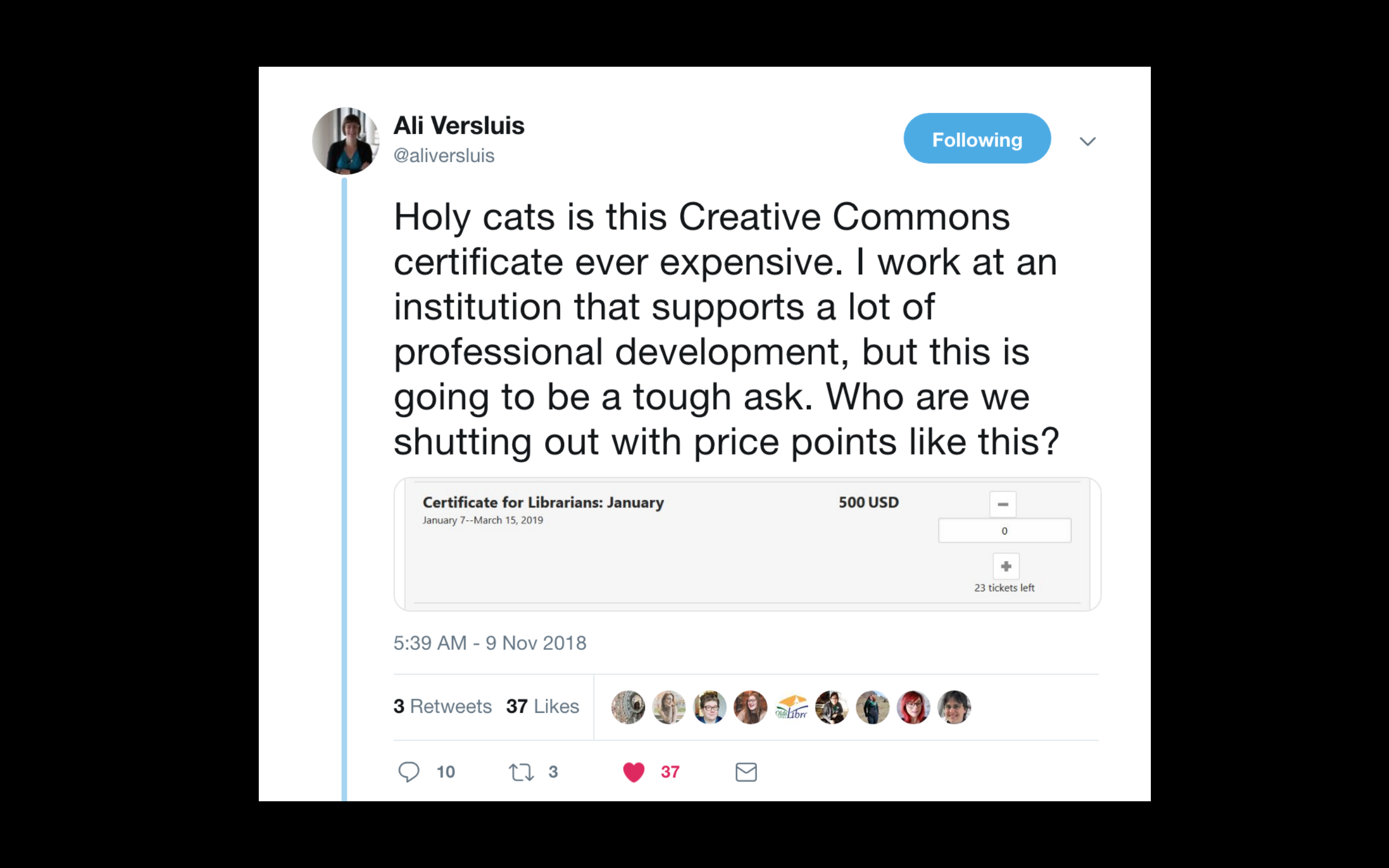

CC itself as a steward of the commons is struggling to find its purpose in the movement. Version 4.0 of the licenses were finished when I worked with them, and they were designed to work well across the globe for ten years after their release. I cannot vouch for the quality or usefulness of the CC certificate program, but now that the program is in its second year, the cost of participation is rising to a point that puts it out of reach of many folks. The lack of meaningful engagement on behalf of the organization makes me concerned about how out of touch they are with the individuals and communities who are actually doing the work, the “commoning”. Pink glittery lapel pins are nice, but the general lack of innovative, inclusive projects leaves me asking questions that have stirred controversy.

As the platforms and organizations that once propped up the movement are shifting and facing a crisis of purpose, the annual gatherings that represent much of the face-time we get with parts of the larger community are putting individuals at risk. Signaling what I choose to describe as a departure from values, a religious keynote speaker was announced as a late addition to the 2017 running of the OpenEd conference. While I absolutely advocate for religious freedom for all who work in open communities, this appeared to be a form of religious colonialism on behalf of a belief system that actively discriminates against individuals who identify as being outside of the binary. Push back from the community after the announcement eventually caused the withdrawal of the keynote speaker, but I worry that we will see similar acts in the future as the memory of it fades.

Only a month ago at the 2018 edition of the same event, there was no Code of Conduct to help guide collegial, professional interaction among attendees. Despite global incidents of misconduct and misogyny in the world that reach to the highest levels of government, the Opened18 Code of Conduct was an afterthought, leaving appropriate behavior among the thousand attendees open to interpretation with real consequences. What’s more, having a Code of Conduct is only the first step, and the hard work actually happens when complaints are raised and the Code is put to the test. The implementation of a code is, like many aspects of our work, a human activity that is subject to the same fumbling and folly that will drive would-be contributors away from the movement. I’m not impressed, and am even less so in terms of the response to critique from the event organizers.

Now, this isn’t to say that it can’t be done well. Not at all, not for one second do I think this is something that is beyond the power of the community. An example of how it has been done well in the past is the Mozilla Festival. Mozfest, as it’s lovingly called, was inspirational for me not only in terms of the ideas and people doing work on the edges of open, but also for its commitment to inclusiveness. All three years I attended and facilitated at Mozfest, Allen Gunn ran a facilitators session that brought the code of conduct for the event to front and center. The shared understanding of what it means to collaborate and treat each other well, and the clear path to deal with things when not all folks could stayed the course, brought an air of safety and confidence to the event that I have yet to see be done better. It’s not easy, but it’s essential.

A theme is emerging here that I hope is becoming clear: human activity is messy.

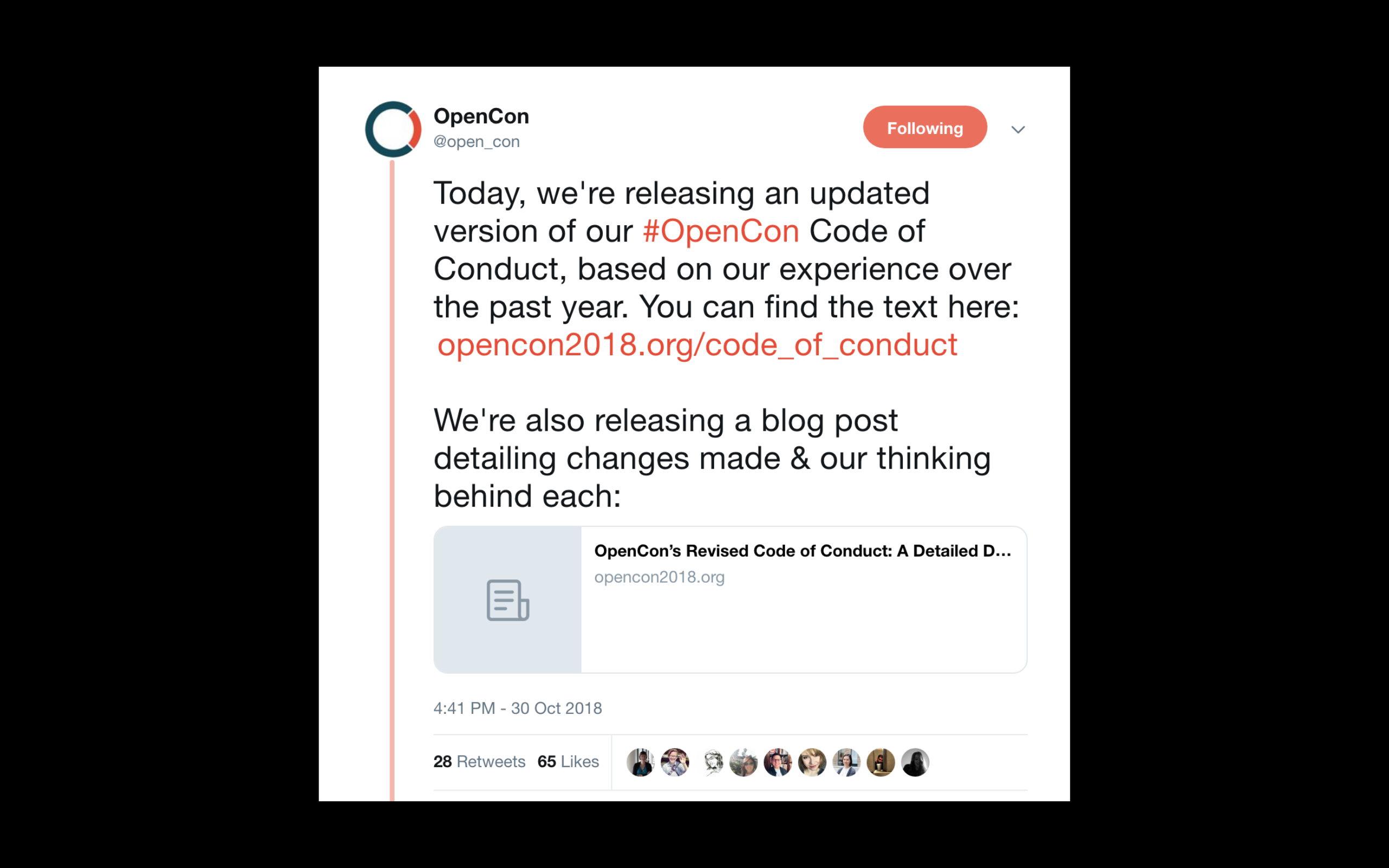

Fortunately, what is emerging from these missteps in the open community are bright areas and examples of leadership that take seriously the messy nature of this work. Only two weeks ago, ahead of the 2018 edition of OpenCon, the organizers took it upon themselves to not only update their Code of Conduct, but also to outline what changes they made to it and functionally what the changes would do to support their event as a safe space.

“As we described in a blog post earlier this month, healthy communities are only possible when the individuals within them feel safe, and an effective code of conduct is essential to providing a safe and welcoming environment for participants—both in-person and online. We recognize that the work of improving the code of conduct and its implementation is an ongoing process, and the changes that we are releasing today reflect our latest thinking on how to work to create a healthy community, as well as our intention to continue learning and making improvements.”

This is leadership needed in many communities, not just open ones, and seeing such forward thinking in our movement is extremely encouraging – it makes me proud to work in this space. If we are to grow this movement and realize the positive change it can bring, more work like this is absolutely needed. This is the kind of work we must do before we can actually get to work, so to speak.

I want to stop here and acknowledge my criticality. If I have offended anyone, I am sorry, but I think we need to be much more thoughtful about how to approach our work that absolutely depends on people. In writing about critical openness, Monica Brown recently reflected on the concept of critical openness:

“Critical openness is a call for challenging questions – ones contextualized in the histories and lived experiences from people around the globe – with the goal of generating productive and meaningful dialogue across power and difference. Critical openness calls us in to find approaches to research and education that are built to serve communities and push forward change…Critical openness runs parallel to open advocacy ensuring that the practices furthered by the open community don’t carry on the very systems that have resulted in the widespread exclusion in the first place.”

As has been said before, a critical movement is a stronger movement. It is when we stop questioning the safety of our space, the intentionality of our actions, and ignore the historical contexts in which we work that people will be left out, or worse.

To bring this talk to a close, I want to let you know that today’s open education movement is stronger than it has ever been, despite its broken parts. The diversity, number of folks involved, and sheer talent that is building in this community is mindblowing, and I think that we are finding the ways forward. But we must be ever-thoughtful. We must be vigilant in our efforts to be inclusive, and to provide safe spaces for newcomers and veterans in “open”. We must remain critical about the structures, processes, and leadership in this movement. And above all else, we must remember that we are taking part in a human activity, one that is messy and beautiful and that I will never give up on.

Thank you.

The header image is a cropped, darkened version of the live sketch Giulia Forsythe did and it can be found on Flickr.