This week marks the final week of instruction at UH, and the end of my first experience teaching a graduate course in Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) in Education.

These days I spend much of my time at work facilitating the development of online programs and courses, with the finally delivery format (usually) being beautiful Wordpress-based courses. But as I mentioned in my last post, I think many online courses are delivered on big learning management systems (LMS) that offer too little bang for the buck of running them. They often are just too much for an independent instructor to spin up and administer, unless they have funding to pay for someone to run things or the skillset to keep the gears turning themselves. Sorry, I don’t want to manage a database; I just want to work on open content with my students.

Now this isn’t to say that LMSs aren’t useful, because they definitely are. At least for some people, for some things that need to be centralized. Being able to manage student enrollment, announcements, a gradebook, and other essentials that need to have privacy is important. But LMSs also tend to be (or turn into) walled gardens, with very little of the learning processes they support being done in the open. Not much ends up living on past the intended delivery period of the course, and student access is lost once they go forward in their educational endeavors. “What would it look like for most of the course to be independent, and shared out in the open,” I wondered. When it came down to stringing together everything for my course, I was happy with how simple (and open) it became despite being distributed across a range of FOSS tools.

Lucky for me, the course had already been delivered twice before (I was in the first cohort four years ago), and the instructional content was fairly mature. Although I had expressed permission from the course owner to reuse it, it was also licensed CC BY-SA, so there was no doubt about being able to take the course and create my own version. So scrape, scrape, scrape I went, pulling content out of the old WP site.

But wait, I thought you were going to tell us about your stack?

Oops! Yes, let’s take a look at that. Or rather, let’s take a look at what I needed my open stack to do for me. Here’s what (more or less) worked:

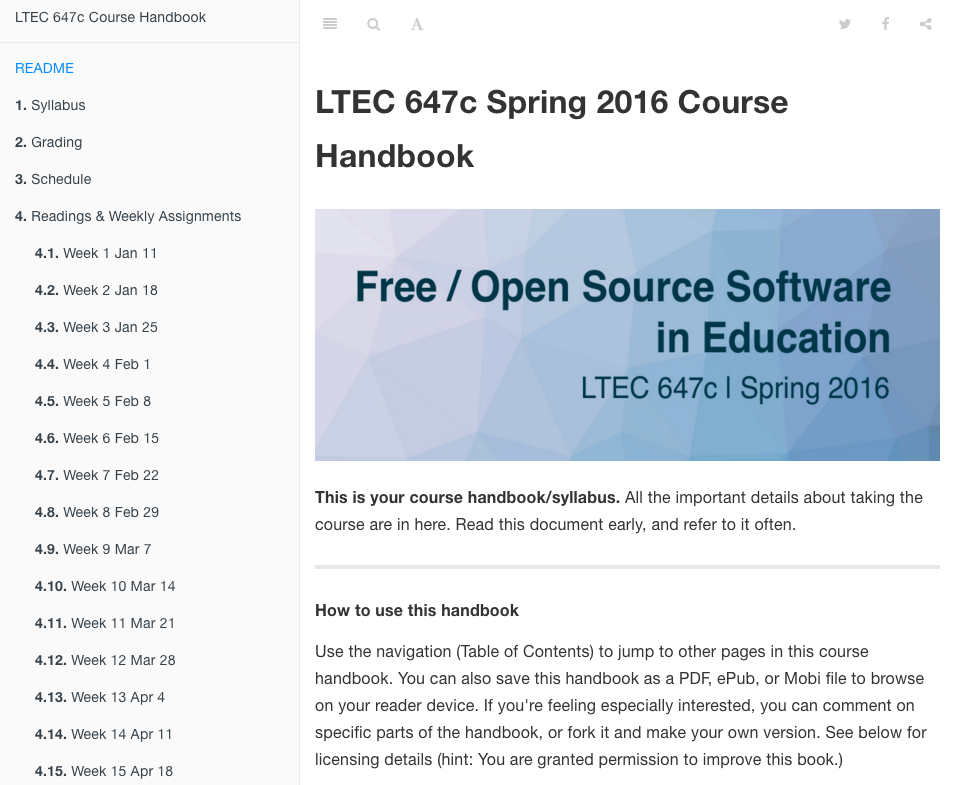

- Course “textbook” content > Gitbooks.io

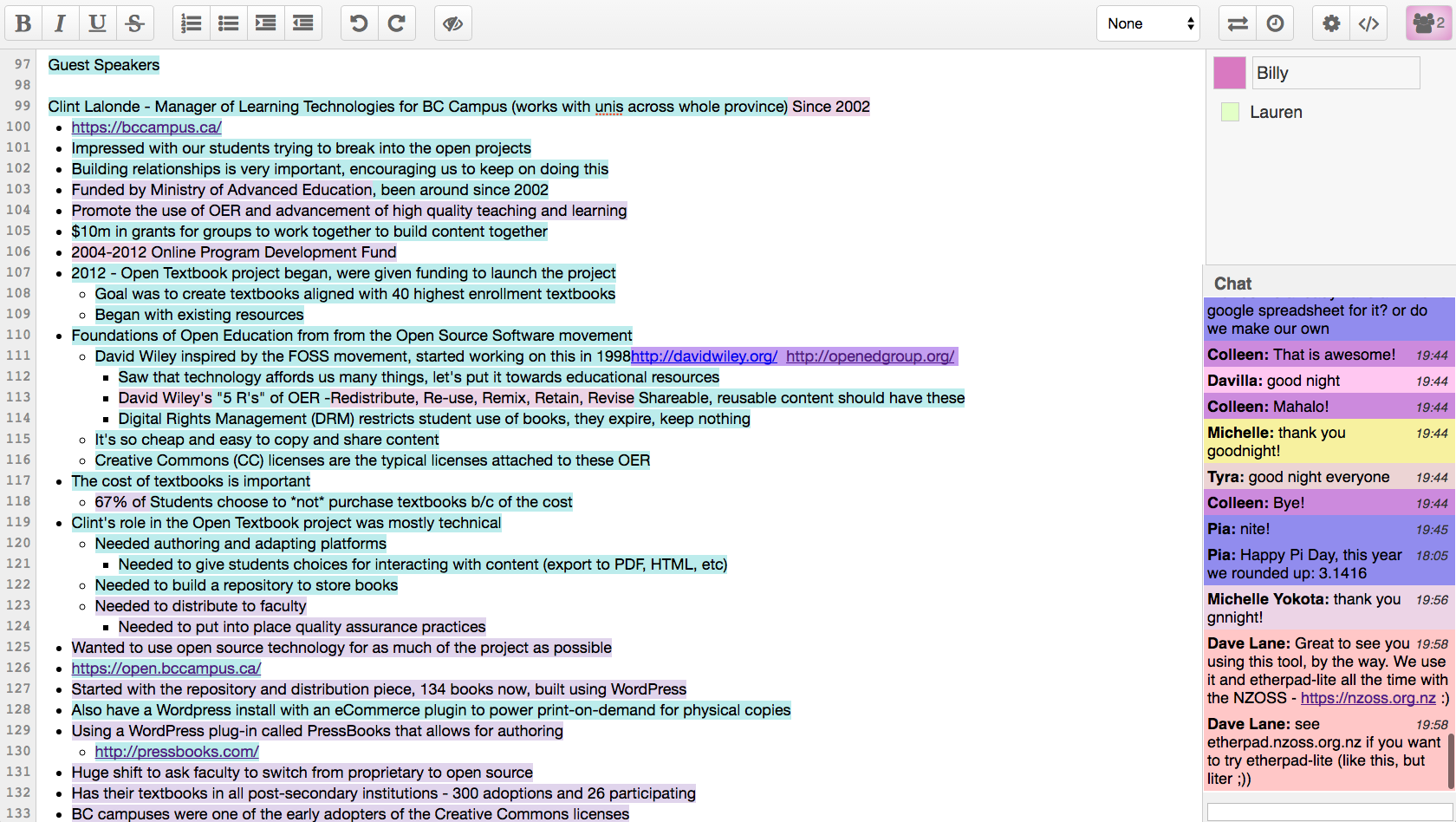

- Class notes > Mozilla’s Etherpad

- Student blogs > Wordpress.com

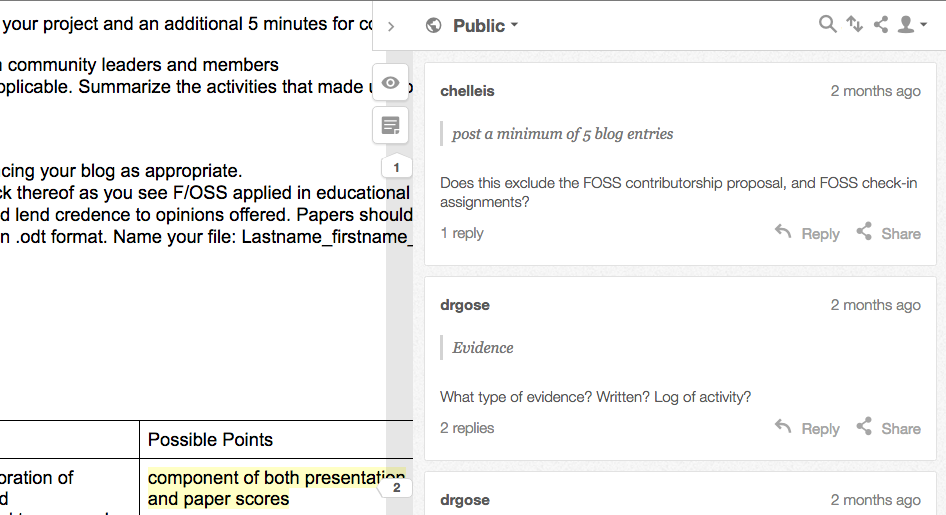

- Assignment annotation > Hypothes.is

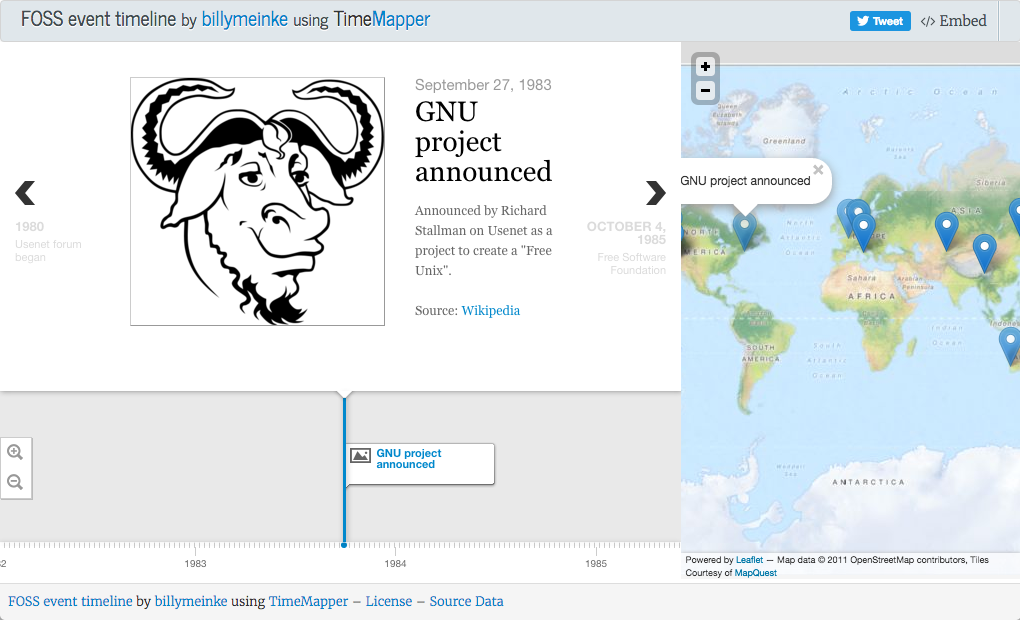

- Collaborative event timeline > TimeMapper

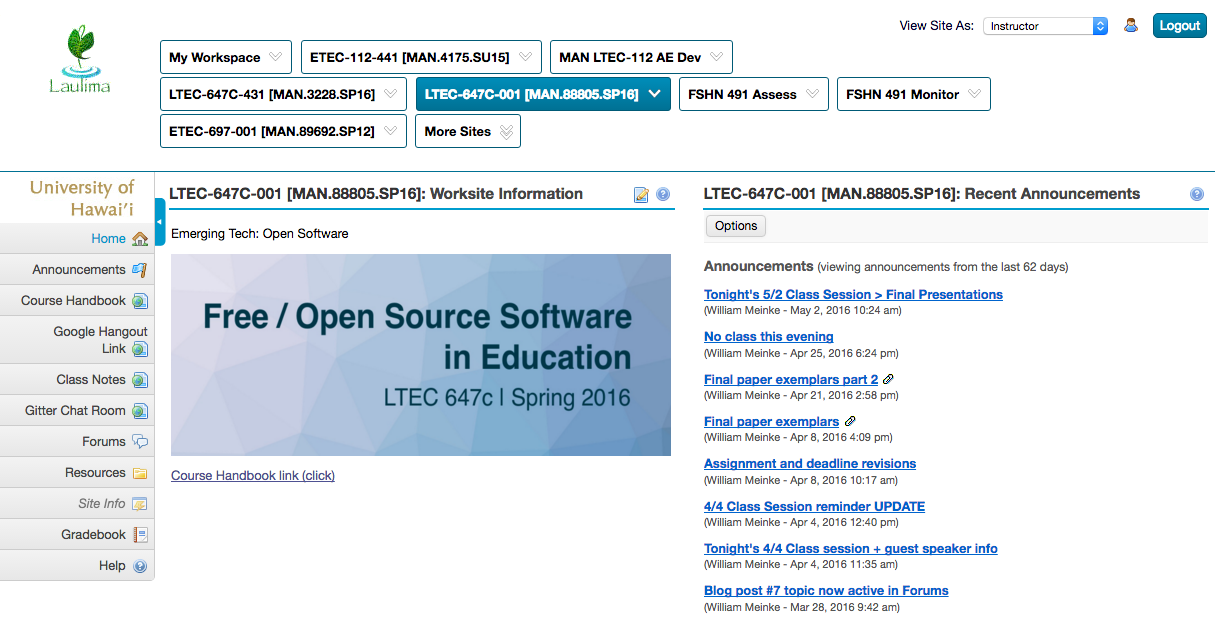

- Gradebook and announcements > Laulima (Sakai)

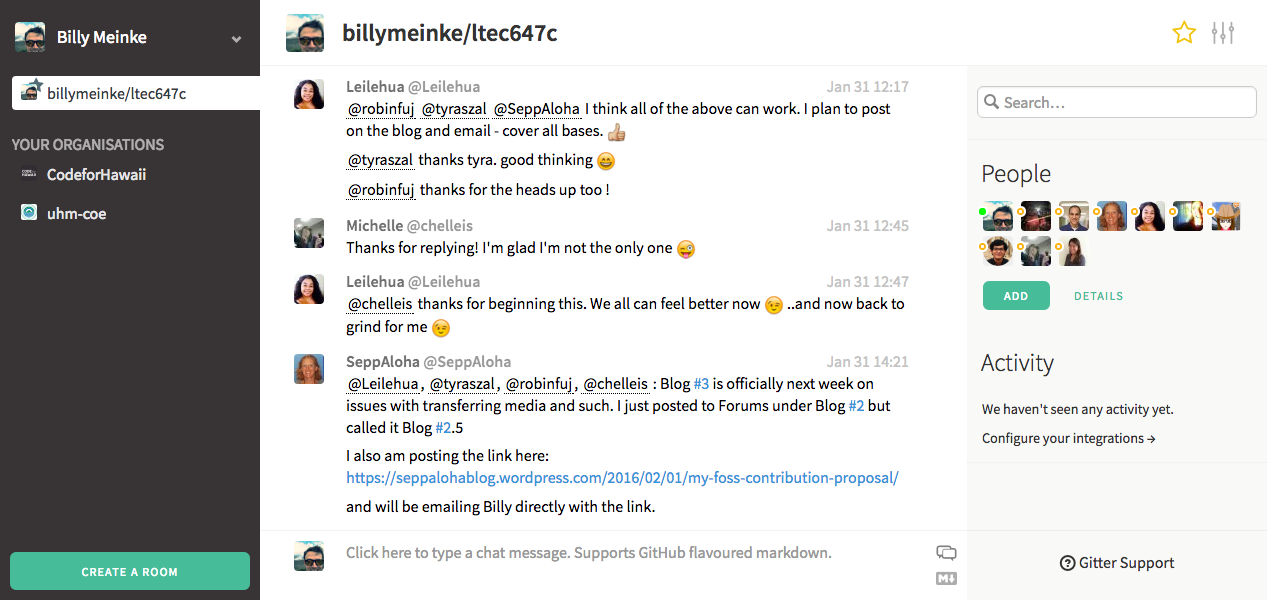

- Live/anytime chat room > Gitter

- Synchronous meetings > Google Hangouts / Blackboard Collaborate

- and many many resources from all over the Web

Let’s dive a little deeper into the what and why of using these tools.

Gitbooks

Gitbooks.io is a pretty amazing tool. It’s a simple way to organize text documents (markdown, actually) into a book-like format, with pages, chapters, links, images, and that’s about it. But other tools offer those “features,” too, ya? Of course. But do the other tools offer version control, forking, and annotation on top of the curriculum? Not as likely. With Gitbooks, students could at any time see the latest changes to the course, see comments/annotations left by other students, and download a copy of the full course content in a variety of formats. The course “handbook” (as I called it) was a living document, setting it apart from most online courses, and it was synced to a Github code repository through Gitbooks. As students caught small errors (which they did) and made suggestions for other readings and interesting material supporting the course topics, they could drop them right into the page. I didn’t end up adding any students as “collaborators” on the course handbook, but they could easily fork it and/or take it with them at any time, in a format that will open on almost any device. Try to do that with your LMS.

Etherpad/Mozpad

As is typical for many open projects, I started an Etherpad document (Mozpad, actually) to record class session notes. This was one of the biggest changes for students in my course, as they had not participated in collaborative note-taking before. Share notes…what the heck? Aren’t we all supposed to scratch down our own notes and not share them? Are we gonna get in trouble for this? Nah, it’s called working open, guys. As a side note, Mozpad doesn’t appear to be very friendly for folks who use screen readers. Still, all the students were able to take part and build a history of the synchronous class sessions that they could all reference as the course progressed.

Wordpress.com

As I think should be done in more courses, students were required to keep their own blog that chronicalled their journey from not understanding what “code” is to contributing to a FOSS project. Each student was tasked with finding a free Wordpress.com theme that would fit their writing style, and house all of their public work on it. I The idea of publishing things they created out publicly was unsettling for some, but I can’t help but wonder what kind of personal transformation took place for each students. By the end of the course, the student writing improved to the point where I got goosebumps reading through their posts. They weren’t afraid to be bold, and it’s literally been months since any of them questioned the idea of publishing their writings openly. At one point in the semester a student asked where they might brainstorm the work for their final project…and I simple told them that the blog was theirs, and to go publish thoughts there. They needed to complete certain work on the blog for the course, but it was theirs to keep and do what they wished with. Don’t let me hold you back, now!

Jekyll/Github Pages

Instead of Wordpress.com, I did anticipate (incorrectly) that some students would be willing to give a Jekyll/Github Pages blog a shot. The idea of blogging out in the open was on its own quite an idea for students to wrap their heads around, and working with a little bit of code was too much. No students ended up using this method to set up a blog, although I did create a boilerplate blog in case the next students are willing to give it a go.

Hypothes.is

The educational applications of the Hypothes.is open annotation tool are just being discovered now, but I had a specific use case in mind for this course. The final project in the course involved students volunteering on FOSS project, offering their time to work on documentation, visuals, translations, and other non-programming tasks for open projects. Their experiences were to be written into a paper and presented during the final class sessions, and the assignment description and rubric was held in a PDF. But that wouldn’t do. So I scraped the content from the PDF, moved it into a Google doc, published it to the Web, and added a link to via.hypothes.is so that students could annotate it without having to install any software locally. Have a question about the grading criteria? Annotate it and let me know. Are the instructions a little hard to understand in some sections? Mark it up and let’s discuss. I announced an open period to annotate the final project description and rubric, after which the students were tied to the document. It was a “speak now or forever hold your piece” sort of situation, and Hypothes.is provided the means for open discussion about the project that would dictate a huge chunk of their course grade. I’ll be doing activities similar to this in the future.

TimeMapper

One collaborative assignment involved the student building a timeline of events in FOSS (and open, more generally) history. TimeMapper made it easy to create a spreadsheet with the proper column headings and make it feed a pretty, interactive timeline. Once the Google spreadsheet (arguably not all that ‘open’) was created, students could jump in an add their three to five events to the timeline, which was updated in realtime. This work will be continued for the next iteration of the course, of course.

Laulima/Sakai LMS

I must admit that there wasn’t a clear way around using the university-supported LMS for some things. I used Laulima (our version of Sakai) for announcements, student assignment submissions, and the gradebook. There are just some things that need to be carefully managed and protected, so for this reason I still returned to our local LMS. I expect I’ll have to do this for some time, even if I scale back my use further.

Gitter

I set up a Gitter chatroom for the course, but I’ll admit that it didn’t have the same uptake with students as I had wished. Some discussion happened there, and the chatroom remained open as a way students could contact me (and the whole class) at any time, but after a while the room stagnated and students stopped chatting there. I imagine Gitter might be a more useful tool if updates (also called integrations) to the course content were fed into it as they are typically done when Gitter is used for coding projects. I’ll have to look at this tool again down the road and see if there’s a way to support more ongoing, lively discussion. To its merit, Gitter has a nice, simple web interface and mobile apps for iOS and Android - And I was able to get notifications when students had immediate needs that were suitable for display to the whole class.

Google Hangouts/Blackboard Collaborate

It’s not worth mentioning much about the web conferencing tool we used for synchronous sessions, since many of them have worked the same way for quite a while. We used Google Hangouts for the first few class sessions, but then hit the 11-person cap for participants in a Hangout, and ended up moving to the new version of Blackboard Collaborate for the last half-dozen class sessions. There isn’t an “open” tool for this I’ve found that works well enough to switch to it.

Pulling it all together

So, that looks like quite a stack. Maybe even more tools that you’d consider using if you facilitated an online course. But let’s keep in mind that an underlying reason for my selection of such a swath of tool is that they allowed me to practice dogfooding. Dogfooding essentially means that you walk the talk, you show others that you will do as you say, and that you eat what you bake. I don’t bake dogfood myself, but I can say that in this course about FOSS, we used FOSS most of the time. It was integrated into almost every activity, so there was little room left for students to feel as if FOSS didn’t impact them at all. I mean, how could I possiblly spend 16 weeks telling students how neat it is to have FOSS to work with, without working with it? That just wouldn’t be cool. So we worked with FOSS.

Next week, the final round of student presentations about their contributorship project will take place, and I’m eager to see them. I have a stack of final papers waiting for me to grade, which I’ll do gladly. When you’re passionate about finding ways to open up processes, to spread the word about open, and to use FOSS whenever there is a reasonable option to, good things happen. At least they have for me: I’ve found that teaching (or facilitating) is a challenging, lovely experience - one I look forward to taking on again.